Overview

This writeup will cover some of the basic techniques and methodologies that one could use to reverse and solve android apk challenges. We will also walk-through some basic ctf challenges from picoGym.

Writeup table of content

- Tools and programming requirements

- What is APK?

- Developer vs reverse engineer

- CTF walk-through

- Conclusion

- References

Tools and programming requirements

Recommended tools to follow through this writeup:

- Android Studio

- decompiler.com

- Android Debug Bridge

- vscode & vscode plugin – APKLab

- dex2jar

- jd-gui-windows

Some understanding basic understanding of Java.

What is APK?

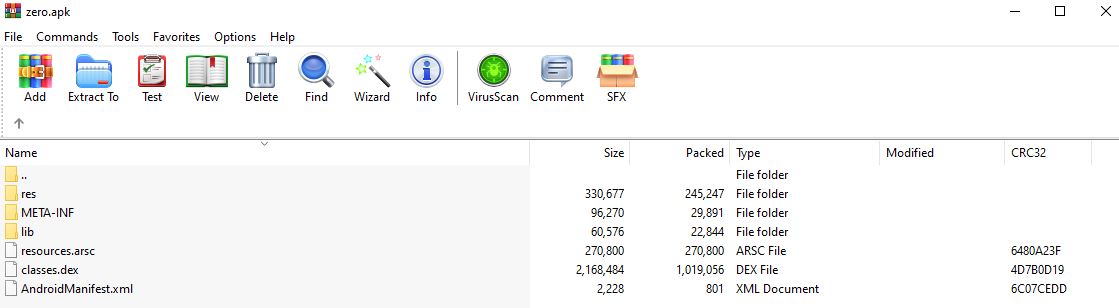

APK is the the Android application package file formatted used by the Android operating system, mainly used for distribution and installation of apps on android devices. It is an archive (.zip) and we could open it in a file archiver tools such as winRAR and observe the package contents of the apk.

Screenshot of an apk’s package content when opened in winRAR

Package content

The apk has a typical file structure of the following format:

- META-INF/

- MANIFEST.MF (the Manifest file)

- CERT.SF (list of resources and a SHA-1 digest)

- classes.dex (Dalvik bytecode)

- lib/

- x86_64 (compiled code for x86-64 processors only)

- x86 (compiled code for x86 processors only)

- arm64-v8a (compiled code for all ARMv8 arm64 and above based processors only)

- armeabi-v7a (compiled code for all ARMv7 and above based processors only)

- assets/ -resources.arsc

- res/values/strings.xml

- AndroidManifest.xml

Those files name in bold are the files that we are usually interested in as they contain the byte source code, the native functions (external functions) and data used by the app.

Developer vs reverse engineer

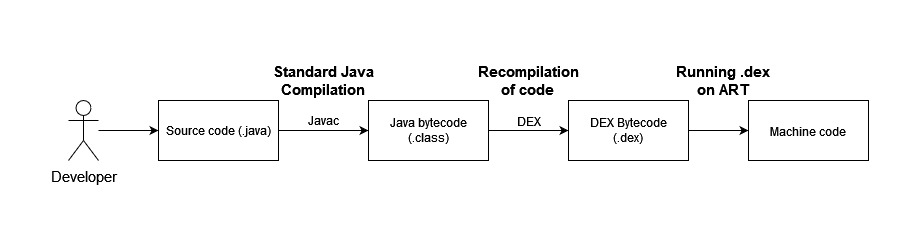

We first look from the perspective of an android developer:

Most of the android applications are written in Java and kotlin. The Java source code written is compiled by Standard Java Compiler into Dalvik Executable (DEX) bytecode format. The bytecode finally gets executed by either one of the two different virtual machines Dalvik and Android Runtime(ART). For earlier versions of Android, the bytecode was translated by the Dalvik virtual machine. For more recent versions of Android (4.4++), Android Runtime (ART) was introduced and in subsequent versions, it replaced Dalvik.

Flowchat of the common steps an Android developer takes

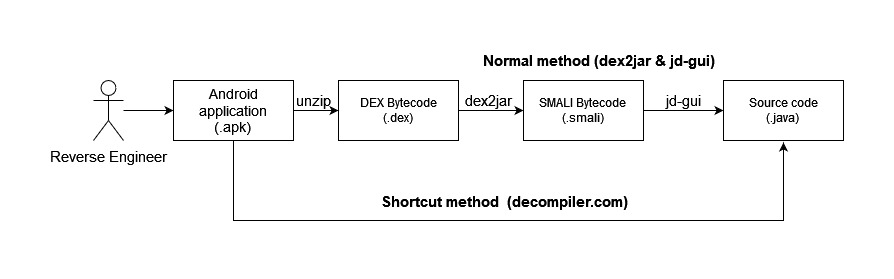

And from the perspective a reverse engineer:

A reverse engineer will do the opposite to restore back the source code. There are generally 2 approaches that one could take. The normal method and the shortcut method.

The normal method will reverse the DEX bytecode into SMALI instructions using dex2jar, you can think of it like the assembly language which is between the high level code and the bytecode. With the Smali code, we could either continue to reverse using jd-gui and obtain the decompiled java source code but we could also modify the smali code and patch the apk to access hidden information.

The shortcut method is a direct method that will decompile the apk into its source code using decompiler.com. This method allows us to quickly obtain the apk source code and its package contents. This is the method that we will mainly rely on for the CTF challenge walk-through.

2 approaches the reverse engineer could take to reverse apks

CTF walkthrough

Let’s take a look at 2 apk reversing challenges from picoGym, we will apply the shortcut method and any additional steps to capture the flags. For the challenges, I will be running the apks in an android emulator Pixel_3a_API_30_x86 via Android Studio. For more information, check out android studio setup and install android emulator. Alternatively, if you have an android device, you could also connect to your computer via USB cable and launch it with android studio following this guide.

droids0

AUTHOR: JASON

DESCRIPTION: Where do droid logs go.

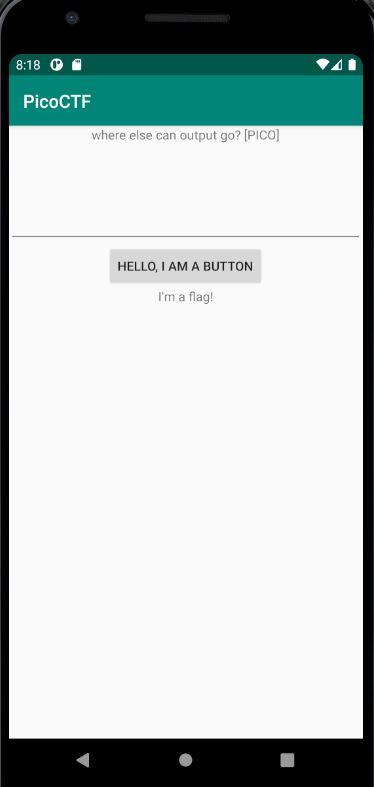

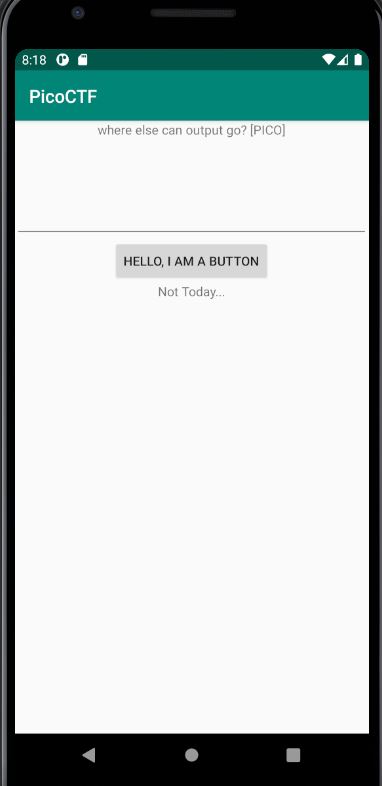

Running the apk

We can start off by opening the apk via Android Studio (File > PROFILE or DEBUG apk) and then running it on our emulator (Shift + F10). The android emulator will launch and the apk will run and display the following main screen.

We can interact with the UI of the app, such as pressing the buttons and check for any hidden drawers. Upon pressing the button, the text below the button changes from “I’m a flag!” to “Not Today…”

It seems like we triggered an event but we don’t get any flag output. Let’s decompile the apk.

Decompile the apk and understanding the code

Using the shortcut method via decompiler.com, we can obtain the source code of the apk:

one of the files that stands out is sources/com/helloccmu/picoctf/FlagstaffHill.java and with the following code:

package com.hellocmu.picoctf;

import android.content.Context;

import android.util.Log;

public class FlagstaffHill {

public static native String paprika(String str);

public static String getFlag(String input, Context ctx) {

Log.i("PICO", paprika(input));

return "Not Today...";

}

}

The getFlag() function when invoked will log the output of paprika(input) and return "Not Today..." which corresponds to what we observed earlier on, it seems like the flag

has been passed into the Log.i() function invocation.

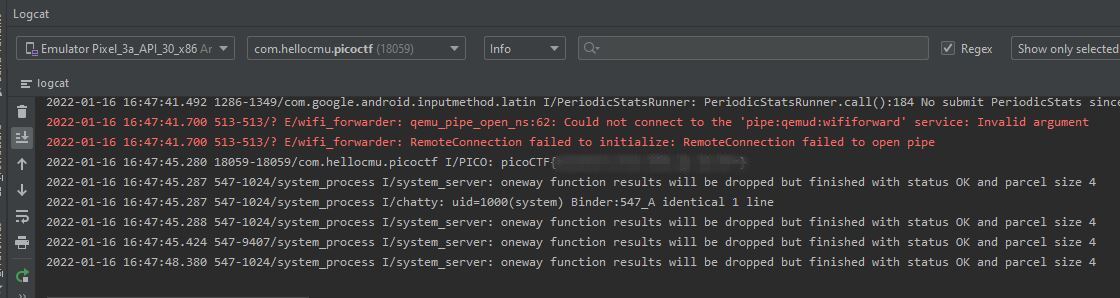

Where does the output of Log.i go?

Log represents the Logger class for Android development, and serves as API for sending log output. There are different levels of problems and information that the developer could tag the log messages. The output can be captured via Android Studio or via CLI logcat.

Get flag

So, to get the flag, we could inspect the log outputs in our Android Studio instance. We can apply the info filter to filter out the irrelevant stuff.

droids1

AUTHOR: JASON

DESCRIPTION: Find the pass, get the flag.

Running the apk

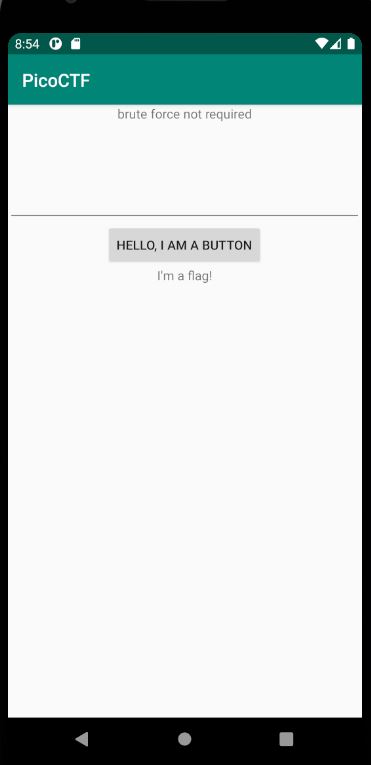

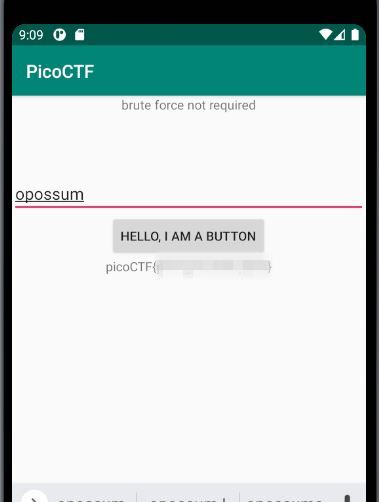

Following the steps from the previous walk-though, we will setup and interact with the UI of the app.

It seems like the application is asking us for a password, if the wrong password is provided, it will output to us “NOPE”

Decompile the apk and understanding the code

Using the shortcut method via decompiler.com, we can obtain the source code of the apk:

one of the files that stands out is sources/com/helloccmu/picoctf/FlagstaffHill.java and with the following code:

package com.hellocmu.picoctf;

import android.content.Context;

public class FlagstaffHill {

public static native String fenugreek(String str);

public static String getFlag(String input, Context ctx) {

if (input.equals(ctx.getString(R.string.password))) {

return fenugreek(input);

}

return "NOPE";

}

}

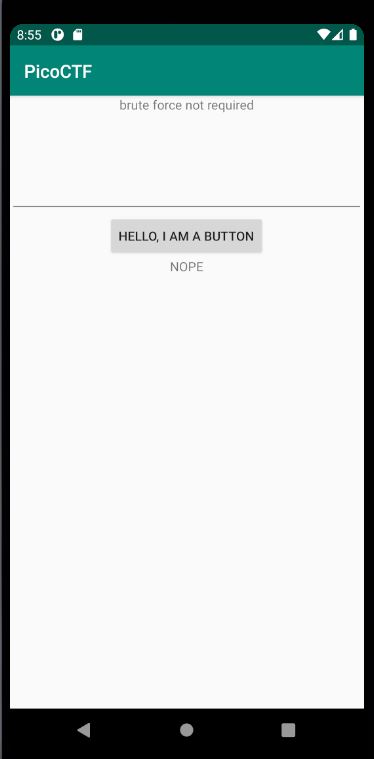

The getFlag() function when invoked will check our input with a password string. If the strings are not equal, the function will output “NOPE”.

Our aim is to locate the password at ctx.getString(R.string.password)) and after some searching within the decompiled apk, there is a suspicious file

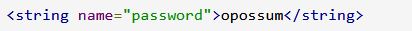

/resources/res/values/strings.xml and it contains a password field with the following data:

Get flag

Try out the password that we restored and obtained the flag!

Conclusion

There are definitely more areas to cover in Android reversing such as apk patching, dynamic debugging & native function hooking and I hoped that you’ve enjoyed reading and learnt something new. If you want to learn more, I recommend trying out different kinds of challenges from picoGym, past ctf challenges and reading up cyber security articles and papers.

References

- https://developer.android.com/guide/components/fundamentals.html

- http://www.theappguruz.com/blog/android-compilation-process

- https://www.ragingrock.com/AndroidAppRE

- https://book.hacktricks.xyz/mobile-apps-pentesting/android-app-pentesting

- https://programmer.help/blogs/smali-introduction-manual.html

- https://medium.com/shipbook/android-log-levels-c0313055fdb9

- https://frida.re/